Dimension: Self-directed learning

Jutta Rump; Imke Buß; Janina Kaiser; Melanie Schiedhelm; Petra Schorat-Waly

Self-control is regularly required of students, be it when writing an academic paper, when acquiring knowledge, skills and applying them or when solving tasks and problems. Modules demand this self-control, i.e. independent and planned action, to varying degrees (Weinert 1982). Particularly in learning scenarios in which students develop or discover something together, external control (by the teacher) is replaced by increased internal control (by the students) (Bruner J. 1973; Schiefele and Pekrun 1996). In addition, learning theories indicate that learners cannot simply store the content presented identically to the presentation and that self-control processes are therefore of great importance (Roth 2001; Spitzer 2007). Learners therefore actively construct their knowledge in self-directed processes (Schubert-Henning 2007). New knowledge must be integrated into existing knowledge structures and interpreted on the basis of personal experience (Mandel and Krause 2001). Learning processes are therefore subjective and individually different.

Wosnitza (2000, p. 39) defines self-directed learning as follows:

"The individual self-directed learning process can be understood as an interplay between volition, knowledge and ability. Applied to an individual learner, this means that they have a certain basic knowledge (knowledge) and are willing (willingness) and able (ability) to plan, organize, implement, monitor and evaluate their learning independently and on their own responsibility, whether alone or in cooperation with others. The environment in which this learning process takes place has a direct and indirect influence on the actual course of this process."

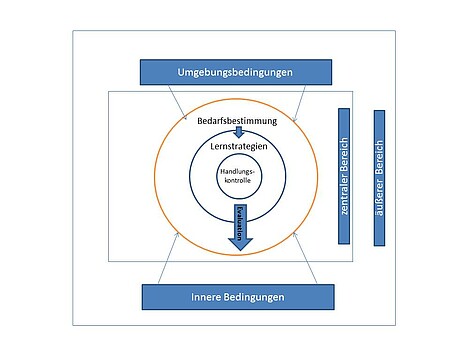

In the "two-shell model" of motivated self-directed learning (ibid.), the complex learning process, which integrates cognitive, metacognitive, motivational and social aspects, becomes clear:

Figure 1: The "two-shell model of motivated self-directed learning

Source: Wosnitza (2000).

The model consists of a central area in which the learning process is described with the basic concepts: needs assessment, learning strategies, action control and evaluation, and an outer area in which the learner-specific (internal) conditions influencing the learning process such as knowledge, abilities and skills and environmental conditions such as learning material, teaching quality, social integration etc. are located. The determination of needs involves the identification of a subjective deficit of declarative[1] and procedural[2] knowledge and is largely responsible for the entry into the learning process. This means that students check what they already know and can do in comparison to the formulated learning objectives. The inner shell contains the processes of information processing, which include the implementation of learning strategies on the one hand and the control of the information processing process through action control processes on the other. The link between the inner and outer shells is the final evaluation. Students have often not learned this complex self-regulation during their time at school. It is important to provide them with continuous support throughout the course of their studies and to reflect self-control in the modules, courses and examinations.

Literature

Bruner J. (1973): The act of discovery. In: H. Neber (ed.): Discovering learning. Weinheim: Belz.

Mandel, H.; Krause, U.-M. (2001): Learning competence for the knowledge society. Research report 145. Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität. Chair of Empirical Pedagogy and Educational Psychology. Available online at epub.ub.uni-muenchen.de/253/1/FB_145.pdf, last checked on 19.01.2016.

Roth, G. (2001): Feeling, thinking acting. The neurobiological foundations of human behavior. Frankfurt: Suhrkamp Verlag.

Schiefele, U.; Pekrun, R. (1996): Psychological models of other-directed and self-directed learning. In: F. Weinert (ed.): Psychologie des Lernens und der Instruktion. Encyclopedia of psychology. Göttingen: Hogrefe (vol. 2).

Schubert-Henning, S. (2007): Toolbox - Learning competence for successful studying. Bielefeld: Universitätsverlag Webler.

Spitzer, M. (2007): Learning: Brain research and the school of life. Heidelberg, Berlin: Spektrum Akad. Verlag.

Weinert, F. (1982): Self-directed learning as a prerequisite, method and goal of teaching. In: Unterrichtswissenschaft (2), pp. 99-110.

Wosnitza, M. (2000): Motiviertes selbstgesteuertes Lernen im Studium: Theoretischer Rahmen, diagnostisches Instrumentarium und Bedingungsanalyse. Landau: Empirische Pädag. e.V (Educational Science, 5).

Citation

Rump, Jutta; Buß, Imke; Kaiser, Janina; Schiedhelm, Melanie; Schorat-Waly, Petra (2017): Dimension: self-directed learning. In: Rump, Jutta; Buß, Imke; Kaiser, Janina; Schiedhelm, Melanie; Schorat-Waly, Petra: Toolbox for good education in a diverse student body. Working Papers of the Ludwigshafen University of Business and Society, No. 6.

Use according to Creative Commons under attribution (please use the citation provided) and for non-commercial purposes.

[1] "Declarative knowledge corresponds to knowledge of facts." For further information, see Wosnitza (2000, p. 84 f.).

[2] "Procedural knowledge is knowledge about how to do something." For further information see Wosnitza (2000, p. 86 f.).